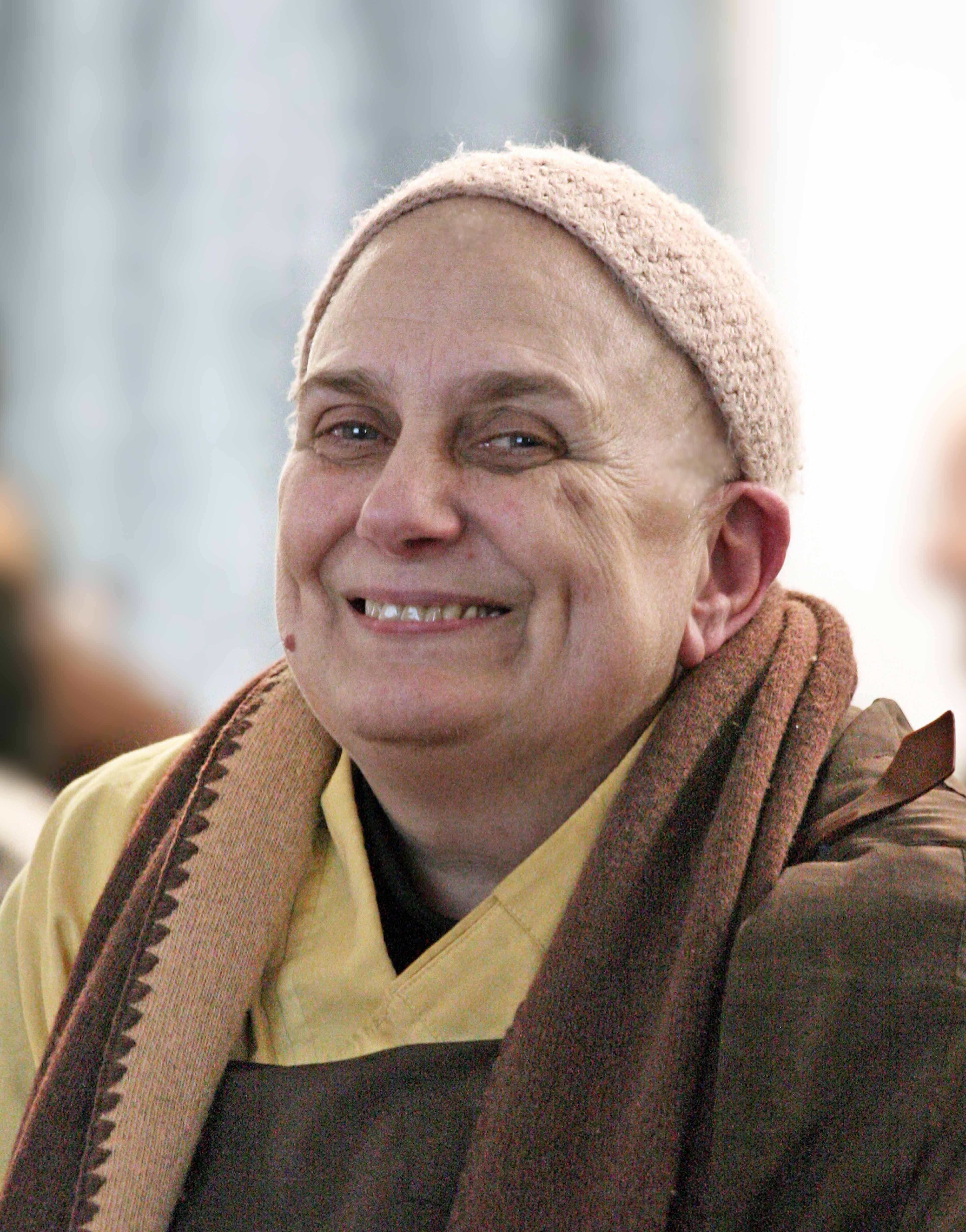

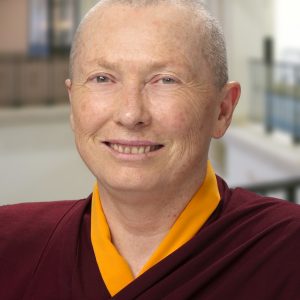

Daughters of the Buddha – Interview with Venerable Karma Lekshe Tsomo

Tell us about yourself.

Oh, how long do we have?

I was born in Delaware, during the Second World War. My family name was Zenn. It was probably a misspelling of a German name, but because I had that name, when I was a little kid, the children at school would tease me about being a Zen Buddhist. So I had to figure out what it was. By this time we were out in Malibu and the nearest library was in Santa Monica. I found two books on Buddhism, The Way of Zen by Alan Watts and Zen Buddhism by DT Suzuki. I read those books and that was it. I was completely… wow! So happy to find the answers to many of the questions I’d had in mind. I declared to my mother that I was a Buddhist when I was about 11 years old. Since that time, I’ve been trying to learn more about Buddhism.

Master Hsuan Hua always asked for people’s educational qualifications. I remember that was the first thing he asked me.

I went to UC Berkeley in the ’60s and studied Japanese, Chinese, and Buddhism. In those days, the major was called Oriental Languages. And then I came to the East-West Center here in Honolulu in 1969 and did a master’s in Asian Studies.

Then I went to Asia for field research for six months but I made it last for two years. The first time I traveled to Asia was actually in ’64 and ’65, to Japan, India, Nepal, Sri Lanka, Southeast Asia. I had been looking for a monastery for women, but I didn’t find one. So I went back to UC Berkeley, graduated, came to the East-West Center, graduated, and then went out for another two years. And at that time I still didn’t find a monastery, but I found wonderful teachings at the Library of Tibetan Works and Archives in Dharamsala, thanks to His Holiness the Dalai Lama, and studied with wonderful teachers.

I went back and forth between Dharamsala and Honolulu to work and to support my studies. In 1977, I became a novice nun in France with the 16th Karmapa. Then I continued my studies in Dharamsala.

In 1982, I was searching for opportunities for full ordination. I knew it existed, but nobody knew where. I remember writing letters to the City of 10,000 Buddhas, and they said they have the lineage, that they give the ordination, and that I could come, spend two years as a novice, and then I could take the ordination. The thing was, I was studying in Dharamsala and didn’t want to interrupt my studies. The Tibetan tradition has wonderful study programs, and I was really into it. Eventually, I was able to take full ordination in Korea in 1982 and went to Taiwan to observe the ordination again, because we were hoping to bring the lineage of full ordination for women into the Tibetan tradition. We’re still trying. It’s not completed yet. We’re still working on it.

In 1989, I got bitten by a snake in Dharamsala and almost died. After three months in the hospital, I came back to the States. I was too sick to go back to India, so I went back to school at the University of Hawai’i, and did another master’s (in Asian Religion), waiting for a Buddhist studies program, which never got funded. So then I switched over to philosophy, got a degree in comparative philosophy in 2000 and got really lucky to get a job teaching Buddhism at the University of San Diego, a Catholic university. I’ve been there the last 20 years, and I’m still there teaching, and that’s my story.

What inspires and motivates you as an individual?

In terms of social justice, what motivated me really was the inequalities that existed in Buddhist institutions. There may be exceptions, but they’re rare. In general in Buddhist societies, Buddhist women hold no positions whatsoever in Buddhist institutions. They’re completely male dominated.

Even though we’ve been working for change since 1987, there are still no women in positions of power in the Tibetan tradition or in the Chinese tradition. In Korea, two nuns hold positions in the Chogye Order, the largest monastic order, but, generally speaking, women’s voices are not heard. So we set out to try to understand more about this. Women were getting very discouraged and very dispirited, having little to eat, no support, and no higher ordination.

Many of the nuns in Dharamsala were illiterate. They’d never had the opportunity to learn to read, especially those coming from Tibet. So I started with a literacy program for 11 nuns. They all learned how to read in two months, even the one who was 63 years old. Then they wanted to learn more, and we added classes one by one: Tibetan grammar, philosophy, and even English. Eventually, we had a full-time study program. So that was the beginning of Jamyang Chöling Monastery and Jamyang Foundation. We started 15 monasteries, and we still support 12 monasteries, as well as schools for girls in Bangladesh for the Marma people along the Burma border.

Meanwhile, we’ve realized it’s not just in the Tibetan tradition that women are disadvantaged, but all Buddhist traditions. Generally speaking, women get fewer opportunities. Positions of power are almost always given to men. So we started thinking that we should get together and talk about it. We thought it would be a little tea party, and it turned out to be a nice big conference in Bodhgaya, where the Buddha achieved enlightenment. His Holiness the Dalai Lama inaugurated the conference, and 1500 people came, mostly to see him, but a couple hundred of us stayed on for a week to try to figure out: what can we do?

We decided that education was key. If women are illiterate, their opportunities for changing society are limited. Even in the worldly sphere, their social and economic opportunities are limited. They get cheated because they can’t read the contracts. So we decided we needed to get into action. We needed an organization to continue the conversation so we founded Sakyadhita International Association of Buddhist Women. We decided to name it Sakyadhita, which means daughters of the Buddha, and have been working ever since to try to improve conditions for women throughout the world.

Jamyang Foundation fosters education projects for women in developing countries, and Sakyadhita is the global network, or alliance, of Buddhist laywomen and nuns, with branches in more than a dozen countries and many projects for research in translation and publication, mostly to encourage Buddhist women, wherever they may be.

A lot of young people are coming to Buddhism and they have these questions. They see this gender dynamic in Buddhism and how women really are treated differently, not only in the institution, but even sometimes in Sutra texts. Do you have any suggestions, or what would you say to people that are struggling with that?

People can begin by reading about the history of women in Buddhism. Lots of free resources are available on the Sakyadhita website. They’ll find all our past newsletters, which talk about the efforts of women in different Buddhist traditions, both in history and today. We also have a number of books there for free download, where people talk about everything under the sun—meditation, ordination, social engagement, and women’s contributions to Buddhism. The history of Buddhism is generally a history of men. Where are the women? We’ve been trying to catch up for lost time and unearth, reveal, and uncover the stories of women in Buddhism.

It’s an ongoing process, and more and more women have become encouraged. Lots of women think we should read and educate ourselves about the efforts that are already ongoing. For example, the ordination issue is very complex. And some people will just make a blanket assumption that Buddhism is sexist because women in many Buddhist countries don’t have access to higher ordination. There’s definitely a case to be made for that, but then we also need to recognize that women in China, Taiwan, Korea, and Vietnam all do have access to higher ordination.

Access to higher ordination seems to correlate with better educational opportunities and better support from the community. That’s my argument. It’s not about power and position. Sometimes people say, “Ah, you’re just interested in power. You’re just interested in position.” That is not our motivation. Our motivation is to empower women to transform themselves, their communities, and the world.

The Buddha gave higher ordination to women, as well as to men. It’s not about worldly achievement. There’s something very profound about ordination and especially about higher ordination. There’s no question that receiving full ordination and observing the bhikṣu or bhikṣuni precepts makes one more mindful. The precepts are very beneficial on the spiritual path.

The last thirty years have been a time of great achievements for Buddhist women around the world. When people go to meet monks, they can ask, “Where are the women? Where are the nuns?” It’s helpful to make the contributions of women an issue. It doesn’t have to be confrontational or challenging. It’s important and meaningful to draw attention to women’s roles and potential in Buddhism.

When we talk with monks about higher ordination, we have to do our homework. We can’t just go in and say, “You folks are sexist.”

We have to know what the issues are. Some lineages were broken, and some lineages were preserved. How did the Chinese get the lineage, and how were they able to pass it on and maintain it over all these centuries? Some detractors will try to discredit the Chinese bhikṣuni lineage by saying, “Oh, that’s just Mahayana,” not understanding that Vinaya lineages have nothing to do with Theravada or Mahayana. The lineages of bhikṣu and bhikṣuni precepts are Vinaya ordinations. If we do our homework and are informed about the history of the bhikṣuni lineage, if we have our ducks in a row, we can have a nice conversation and help to educate monks who may not have had the opportunity to think about these issues or might not have access to the information.

Translation has been another part of our work. Every two years, we’ve held an international conference on Buddhist women. We had no option but to conduct the conferences in English, and so we have tried to provide translation into as many languages as possible. We’ve tried to make the conferences as inexpensive as possible so that as many women as possible can participate. And we’ve tried to sponsor those who otherwise would not have an opportunity to attend the conferences.

These conferences have really changed Buddhist history, and they’ve been ignored not only by the Academy, but also by many Buddhist organizations as well. It’s interesting to question why. I know in some cases, monks have discouraged nuns and laywomen from going to the conferences and have discouraged women, laywomen, from going to the Sakyadhita conferences. What’s so threatening about women?

Yeah, change is hard for people. There’s a lot of resistance to change.

Change is difficult, but change is inevitable. This is a very basic Buddhist teaching, right? The Buddha didn’t just teach for men. He taught for all sentient beings, including women. But women themselves need to step up and take these opportunities seriously and not be reluctant to study and to teach.

Many nuns think, “Oh no. I can’t teach. I’m not qualified. Let the bhikṣus teach.” For women, not just in Buddhism, it’s a common theme that women relinquish their power willingly.

It’s interesting because the Buddha’s teachings are actually very empowering in a way, because you’re really asked to trust yourself and trust your own abilities and that what you think and how you view things is inherently of value.

Right. We need to trust our own Dharma wisdom. If we’ve studied properly and we know something about Buddhism, then we can try to make change in constructive ways based on Buddhist principles.

For example, at Dharma Realm Buddhist Association, you have monks and nuns on both sides of the Buddha Hall. For a very long time at most monasteries around the world, the bhikṣus stand first, then the novice monks, then the bhikṣunis, then the novice nuns. Sometimes women can’t get in the room to hear the teachings, or they’re on a lower elevation, but at the City of 10,000 Buddhas, for at least 30 years, monks have been on one side of the hall and nuns on the other side. This arrangement has been instituted in a number of temples, but not all. Somebody spoke up, I assume, and questioned the patriarchal status quo. Gender equality is sensible, so there didn’t need to be a demonstration or a revolution. Sometimes people just haven’t thought about these things. For example, in the Tibetan tradition, the nuns weren’t wearing the yellow robe for ceremonies, and I just asked His Holiness the Dalai Lama why the nuns weren’t wearing the yellow robes. And he said, “They’re not?” He wasn’t aware that they weren’t. And that very day, he instructed the nuns to wear the yellow robe. It was that simple.

Another time, I asked him why the nuns weren’t attending the Great Prayer Festival. “They’re not? Why not?” he said. And that very day, he instructed the people in charge to allow nuns to attend the Great Prayer Festival. Just by asking the question, it was a simple fix. And now everybody can attend the Great Prayer Festival.

How does the Dharma come alive for you in your life and in your work?

Dharma comes alive every time I sit down to meditate and get in touch. I feel so fortunate to have access to these brilliant teachings and have the time and opportunity to practice. Practice is very inspiring to me. It brings it all home, into the present moment.

Dharma comes to life for me when I’m working with people and try, as best I can, to implement Dharma principles in all these projects. Working in the world is often complicated. People have different motivations and different objectives. When we work in the world, which we can hardly avoid, you have to deal with mechanics and telemarketers and many different kinds of people. If I can diffuse a sticky situation by trying to maintain Buddhist principles, that’s Dharma in action for me.

Dharma comes to life for me when I’m working with people and try, as best I can, to implement Dharma principles in all these projects. Working in the world is often complicated. People have different motivations and different objectives. When we work in the world, which we can hardly avoid, you have to deal with mechanics and telemarketers and many different kinds of people. If I can diffuse a sticky situation by trying to maintain Buddhist principles, that’s Dharma in action for me.

I think every moment is an opportunity for illumination. I mean, just looking at a tree. You see it with full awareness instead of seeing it as a commodity. That’s very, very, very lovely.

How do you find it integrating Buddhist practice with teaching in an academic environment? Do you find that they go well, or how do you kind of balance?

Teaching at the university is a marvelous opportunity. I never expected to do something like this in my life. I just wanted to be a nun and learn Tibetan. Those were my only goals.

Yet somehow, I became a professor at a Catholic university. It’s a wonderful chance to bring Dharma to the wider community. Very few of my students are Buddhists. Most are Catholic or undecided or are not even interested in religion. But to be able to share with them the Buddhist teachings is a fantastic opportunity. No matter what their religious background or their experience, they all seem to pick up on certain principles, like the practice of meditation, conflict resolution skills, and deep listening skills. And, hopefully, they’ll learn something about Buddhism along the way. Then maybe they can go out into the world and help correct lots of misconceptions about Buddhism—that Buddhism is nihilistic, or it’s depressing or something like that. Whether they’re Muslim or Hindu or Christian or whatnot, hopefully they can share the light.

Of course, you have to put up with a lot of department meetings and grade a lot of papers. That is rather boring, but it goes with the territory.

Having a teaching position has given me the institutional support to do research projects and also socially engaged projects. For example, through the university, I’ve received travel funds that have enabled me to travel throughout the Buddhist world, to learn more about the conditions and the perspectives of Buddhists, especially the women, in different countries. That’s allowed me to organize the Sakyadhita conferences every two years, to publish articles about women in different Buddhist societies and cultures, and to meet the most wonderful people. We now have an international alliance. I’m in touch with friends in Siberia and in different parts of the world all the time. We’ve created links around the world that are very enriching, culturally and intellectually, and in terms of Buddhist practice also.

Learn more about Venerable Karma Lekshe Tsomo’s work!

www.jamyang.org

www.sakyadhita.org

hawaii.sakyadhita.org