Cultivating Wisdom and Compassion in Precarious Times

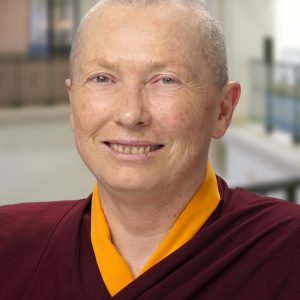

A keynote speech given by Venerable Karma Lekshe Tsomo on May 22, 2021. The video is also available on Youtube.

It’s difficult to even conceive of something unique and valuable to say after all the articulate expressions from the heart of so many wonderful students and faculty!

I’m coming to you from the North Shore of Oahu, about 5,000 miles away, and the birds are singing sweetly and greeting and saying congratulations to all of you graduates.

I think it’s important to set our intentions before each action, before each day, and now, for the rest of our lives. We live in perilous times, politically, socially, economically, environmentally. It sometimes feels quite overwhelming. Recently, I saw a cartoon. There were two dogs talking, and one said, “I heard that the world is going to the dogs.” And they were quite excited about that. It was quite cute.

By some measures, the world situation is getting better, and by other measures, it’s getting worse. Still, overall we can’t deny that the world’s in something of a mess. And this is the perilous time that we live in. And for you graduates, I can only imagine venturing out into a very unpredictable world.

What can we do? Well, fortunately, we have the Buddhist teachings to guide us in these perilous times. You’ve all been so fortunate to spend time at Dharma Realm Buddhist University and the City of 10,000 Buddhas. You have so much knowledge and cultivation now to meet these challenging times. The Buddha was really wise about all of this. His teachings prepare us for exactly the kinds of disasters that we face today. He taught us about dukkha.

Why are we surprised when we run into sufferings and dissatisfactions? That’s life. That’s being trapped in the wheel of samsara. Why get too upset about it? We just recognize, “Oh yeah, the Buddha was right.” He taught that everything is anicca, unpredictable, impermanent, and fleeting. This is also very helpful advice for the present time. People were starting to wear masks, and now they’re starting not to wear masks. Everything’s changing day by day, even the advice we get from the doctors and from the government. Just as the Buddha said, everything is impermanent.

And then there’s the teaching on no-self. I think it’s also so valuable in this time. It reminds us that we’re insubstantial. This is a good reminder so that we hopefully don’t cling so tightly to all of our preconceptions, especially our preconceptions and misconceptions of the self.

So we have all of these tools in hand, all of this Dharma wisdom, and of course, the cultivation that helps us to integrate these teachings in our mindstream. That’s so important. Leaving the teachings in the books on the shelf doesn’t help too much. It’s inspiring, but what really transforms our lives and our world is when we try to put these into practice. And now we have this great opportunity. For all the suffering and hardship that people are experiencing, the pandemic is also, in a sense, an amazing opportunity to verify and go further with the Buddha’s teachings.

In the Mahayana tradition, we can distill it down into wisdom and compassion. We have the wisdom of the Buddha to help deal with all of these catastrophes. And we also have these tools, this prajna, wisdom, and understanding to deconstruct the self and understand the true nature of ourselves and all phenomena on a day-to-day level. This is immensely helpful. We can use our own Dharma wisdom. You’ve studied so well for years, and you’ve presumably passed the exams, so now we take this Dharma wisdom into the world. Every time we need to make a decision, we have guidelines to help us make these decisions. We have a spiritual community that we can consult with to help us make really tough decisions sometimes. You’ll see what I mean when you get out there in “the real world.”

Compassion is also so valuable. Wisdom helps us to overcome our self-grasping and grasping at ourselves as being ever-so-important—so much more important than anyone else. We can relax with that, open some space so that we don’t have to cling so tightly to ourselves. Letting go of clinging to oneself releases tremendous energy that we can use for other things. And this is paired with letting go of the self-cherishing attitude. This is the compassion piece.

We can develop compassion, not only praying to some ideal outside ourselves, but actually internalizing compassion and becoming compassion. We begin to realize that we are just one of many sentient beings, one of almost eight billion human beings, not to mention the billions and billions of animals and other sentient beings. Relaxing our obsession with ourself releases so much energy that we can use for good in the world. By overcoming this obsession with self, we then can use that energy to help others in small ways and large ways, by choice.

So what advice do I have? I can just offer a few little bits and pieces that I hope might be useful. One is, of course, as so many have expressed: gratitude.

Gratitude is appreciating all of the privileges, advantages, joys, and opportunities that we have had and still have. It’s been scientifically proven that gratitude is one of the key factors in keeping a happy heart. So, being thankful actually brings joy to our heart. And when we have joy in our heart—and express that joy in everyday life and every action—that is a great benefit to those around us, many who are trapped in suffering. Even just a smile can really help brighten their day.

I think the important thing for each one of us is to do our best. And, of course, recognize that everyone is doing their best under the circumstances. Everybody is facing difficult circumstances, and some of them are facing great hardships. It’s unimaginable how difficult it must be for the children trying to learn online and the parents trying to juggle three jobs—as teacher, as parents, and also trying to make a living. Imagine how difficult that can be. So, we can appreciate that everyone is doing their best under the circumstances. Another important thing to remember is to let go of our illusions of perfection. We all want to do our best, but sometimes, we’re striving for an ideal that is difficult for an ordinary being to embody.

Only a perfectly awakened Buddha is completely perfect, right? Meanwhile, on the path, we have imperfections. I think this has been one silver lining of the pandemic—that we’ve all had to recognize our limitations. We’ve had to get content with imperfection. Our papers are not as good as we might have hoped, and our responses to difficult situations may not have been as skillful as we had hoped, but we can be comfortable nonetheless. We can be content. Remember, the Buddha said that contentment is the greatest wealth. And he wasn’t talking just about material things. Here I am, living off the grid and looking out over the landscape and living the simple life and being content, but there’s also a kind of contentment that comes from recognizing that we are doing our best under the circumstances. And that’s the best we can do for now.

At the same time, we can also recognize that we have infinite potential—seriously, infinite potential. In the Mahayana teachings, the Buddha made this perfectly clear. We have the potential for perfect awakening. We can learn much more than we think we can learn. They say we only use about 3% of our brains. We could really use much more. We can learn as much as we want to learn. Maybe we have to do it in measured steps. Sometimes I’ve tried reading a book, and I can’t make sense of it. But I come back to it a year later and read it from cover to cover. Quite amazing.

I must state where I’m coming from. Isn’t it the trend now to recognize your social location? So, I have to say I’m American. I was born in the United States during the Second World War. And the gift that my parents gave me was that our family name was Zenn. Because I had this name, the kids at school would tease me about being a Zen Buddhist, and I had to figure out what it was. Recently, I found a copy of the very first books on Buddhism that I read: The Way of Zenby Alan Watts and Zen Buddhism by D. T. Suzuki. At the age of 11, I was fortunate enough to set out on the path of Dharma. It was not an easy path because in those days, there were no monasteries in the U.S. If there were Buddhist teachers in the United States, I certainly didn’t encounter them; I had to go to Japan. When I was 19, I went to Japan to go surfing actually, but once the boat landed in Yokohama, and after it started to snow, I found a monastery. But I didn’t find a teacher. It was a long path to finally find qualified teachers and circumstances where I could study further. And I’m so very grateful for that.

What I learned through all of this is that we really can learn as much as we wish to learn. Again, setting our motivation, we can learn as many languages as we want. There’s a time when people thought if you learn more than one language, it would get you confused. But now they’ve found that learning more than one language actually helps to make our minds more flexible. People who are bilingual are able to code switch very easily. And that’s a tremendous asset in life, to be able to adapt to circumstances in addition to opening our minds to other worlds, ways of thinking, ways of acting in the world, and of course, opening the treasure trove of the Buddhist teachings in different languages.

There’s much more that we can learn, but there’s also much more that we can do in the world. Now you’re equipped with all of this knowledge and all of the skills you need. With this knowledge and these skills, when we go out into the world, we have the potential to do tremendous good. Now, this will be a different path for each person. We don’t need to put people into little cubbies and make everybody do the same thing. When I was studying in the early days, the best option was to be a monk or a nun. It was kind of the ultimate. It was kind of the only real thing to do. If you’re really keen on Buddhism, then you’d naturally want to be a monastic. Over the years, I think we’ve come to recognize that people can be very good Dharma teachers, even as laypeople, as long as they keep the precepts. So we can choose our path, to be a lay person or a monastic, to work in the monastery or to work in the world or both. We can do much more than we imagine.

In fact, we’re already doing so much. We change the world with every thought, every word, every action that we do. Imagine. All actions of body, speech, and mind each have a ripple effect that not only changes our mind and leaves imprints on our stream of consciousness, but also ripples out to all sentient beings and the whole planet. Each plastic bottle we buy and discard has an effect on the world. We can’t ignore our power to have an effect in the world. And let’s hope that it’s beneficial. For example, sometimes I say,”Oh, I’m getting too old. I cannot do any more. I’ve done what I have to do.” But actually, we can do good in the world any time. It’s never too late. It’s never too late to help transform the world, or as we said in the ‘60s, “to save the world.” I’ll never give up.

One of my teachers, Ven. Shig Hui Wan (Dharma Master Xiaoyun), was a nun originally from China. She was the first monastic to teach at a university in Taiwan. And she was a woman, a nun. Later, at the age of 76, she set out to start the first Buddhist university in Taiwan, Huafan University, which is still one of the major universities in Taiwan. Imagine beginning such a project at the age of 76. I’m 76 now myself. And it’s just mind blowing to imagine that someone could undertake something so monumental, and, in the end, be successful at it. So, a long story, but really just the very concept that one person, as Gandhi said, can change the world. And definitely, each one of you can.

I mentioned that my family name was Zenn, and that was a birthright. I realize now what a gift it was to have a name that took me directly to the Buddhadharma. Many people struggle even to make contact, but we create imprints that then enable us to make links with the Dharma again in the future. It’s very important to make these connections—connections with teachers and with texts that will ripen in the future. There is even a story in Tibet about a monk who tripped a Lama. You know, Lama means teacher, right? So he went to see a Lama teach, and he wanted to make a connection. He actually stuck out his foot and tripped them. And so, they say make a connection—sometimes good, sometimes bad—but make a connection because these connections will bear fruit in my future. It’s just a story but…[laughs]

It took me many years to find a teacher and even longer to find a monastery because in those days, back in the ‘60s, it was very difficult to find a monastery for women. In the end, I had to create my own. In Dharamsala, there was only one monastery at the time, and it was full. So I found some old mud huts in the forest, and we began Jamyang Choling, which today has about 115 nuns and has produced some of the first scholars of philosophy, geshes, in the Tibetan tradition, in history, ever. I don’t take credit for any of that, but I’m glad that I could help kickstart the nuns’ education.

Then I encountered a little obstacle. I was bitten by a snake in 1989. I was looking for land because we were being evicted from those mud huts in the forest. And I needed a place where the nuns could continue to live and study. While walking in the forest, I apparently was bitten by a poisonous viper. I say apparently, because I didn’t see the snake. But later the doctors, the experts who examined me told me. This is a reconstructed arm, and I’m lucky to have it. When they took me to Delhi after eight days to get some proper medical treatment, they were going to amputate my arm. And as it happened, they decided I was too serious to operate on, and that I would die, and they might get blamed for it. So they just left me lying there, thinking I was definitely going to die. But I fooled them. And after two weeks, I regained consciousness, and somehow managed to survive that snake bite. After three months in the hospital, it took another year to learn to use my arm again. And I’m so grateful that I managed to survive.

There were many takeaways and many lessons that I learned from that experience. First of all, of course, was impermanence. I’d been studying about impermanence in the texts; I could recite the definitions. We debated philosophy in Dharamsala for six hours a day, so we have very precise definitions for all these terms. I was familiar with the concept of impermanence, but there’s nothing like facing death, moment to moment, for three months, not knowing from one day to the next whether you’ll be alive tomorrow. It really brings home that lesson in impermanence.

The second thing I learned was suffering, of course. I was in incredible, intolerable pain from morning to night and through the night. The Buddha’s teachings on dukkha were no longer merely theoretical, but firsthand reality. That experience was very valuable. Of course, I wouldn’t wish a snakebite on anyone. And hopefully, everyone will manage to avoid pain in life. But that’s a bit unrealistic.

We can benefit tremendously by recognizing that dukkha is a reality in life when we’re younger, instead of waiting until old age, when it becomes very obvious. With arthritis, every step is painful. If we recognize the reality of dukkha when we’re young, we can do something to mitigate the circumstances by understanding it. We can practice in ways that will help us avoid suffering in the future, hopefully, through gaining liberation.

I also learned a great deal about my own practice. I started doing what I thought was meditation when I was a kid. I’m not sure I was really meditating. I think it was just mental wandering. But I had been meditating for many, many years. And yet, when you’re in tremendous pain, facing death moment to moment, stuck in a hospital—I was lucky to be in the hospital at long last, with my arm still attached. That was fortunate. But what I learned was that focusing the mind is not so difficult when you’re well-fed in a nice, comfortable environment with a nice comfy cushion and nice Dharma friends surrounding you. Meditation is a joy, in fact. It’s easy. It can be quite easy. But it’s quite a different thing to focus one’s mind when you’re in agony. You’re in torture. And you’re in a circumstance that’s totally unpredictable, even getting a glass of water in that hospital. You can lean on the buzzer all day, and nobody shows up.

So keeping one’s mind focused takes practice. It takes a lot more meditation experience than I recognized. Not only the pain, but they give you drugs. They give you mind-altering substances: all kinds of painkillers and things like that which cloud the mind. On a good day, an ordinary day, our minds can be quite clear. If we put our close attention to it, we can focus. But when you’re in a hospital, and they’re giving you a whole handful of pills, it’s different. You don’t even know what’s in them. One day, I said, “Oh, what are these?” “Oh, no problem, it is only valium.” I said “Valium! Valium’s bad for the mind.” And then I told them I didn’t want to take it. That helped to clear up the mind a bit.

The other thing that I learned was the kindness of strangers. At that time, our nuns were very young. They didn’t speak Tibetan, and they didn’t speak English. We were communicating in a few words of Hindi, but it was still very nice to have them in the room. In Indian hospital rooms, you’re allowed to have your family and friends with you. So the nuns would sit and chant and meditate all day. That was tremendously comforting. But in terms of medical procedures and so forth, it was not easy.

One time, I remember they hauled me out of surgery—I had umpteen surgeries—and they thought I would die. I was all blue. They really had given up hope. They wheeled me back into the room. At the foot of the bed were three figures. I thought they were angels. Actually, they were angels. They were Indian artists who’d heard the story of the American nun who got bitten by a poisonous snake and was in this hospital. They walked in off the streets to donate blood to me. Can you imagine? And these were the days before AIDS testing. So I lucked out again on that one. Because I was taking transfusions from wherever they could find them. The kindness of strangers walking in off the street to donate blood to a total stranger—that is incredible.

The other boon that I gained from this horrific experience was to awaken to the present moment. This was actually after I got out of the hospital and somehow managed to get back to the States. After I managed to get out of the hospital in Tijuana, Mexico, that a well-meaning friend had put me in (Details upon request. What was she thinking?), I awakened to the beauty of each present moment. Here I was, alive against all the odds, and every flower, every leaf, every bird chirp was so incredibly beautiful and powerful. I was just delighted. It was kind of like a mini Pure Land. So, awakening to the present moment. We often think of liberation and awakening as some distant goal. We pray to achieve awakening in order to liberate all beings from suffering. But we can also, and this is important—you’ve no doubt learned it, but I’m here to restate it—awaken to the present moment. The past is gone. It’s over. It will never come again. The future is not yet to come. It has not occurred yet. It doesn’t exist. All that really exists is this very present moment. Moment to moment. Got it?

And these present moments are fleeting. They’re passing by as we speak. If we do not pay attention, we lose them. We lose those opportunities for awakening, pure awareness, and bare attention. We want to wake up to each precious, present moment because it will never come again. Not only on the cushion, which we should also do, but in everyday action, moment to moment. Respectful listening is a good practice for being in the present moment—paying careful attention to our partners, our children, our parents, our teachers, our friends, total strangers, the homeless. Stop and listen. Each one has a story to tell. You can really make their day if you just take a few minutes to listen. These lessons were really important for me. The whole experience, which could be considered the disaster of a lifetime, and it was, in a sense, was also a great gift for which I’m very grateful in the strangest of ways.

We want to ask ourselves, how many sentient beings have we helped today? Sort of like the Boy Scout motto. We should do a good deed every day. But the Buddhists might say, “How many sentient beings have we helped?” How much goodness have we brought into the world today? How many lives have we touched today? How many people have we made smile today? These tips might be useful when going out into this crazy world.

In the Mahayana Buddhist tradition, we talk about bodhicitta. We talk about “wishing bodhicitta” and “engaging with bodhicitta.” Wishing bodhicitta is the aspiration, this fantastic aspiration to achieve the state of perfect awakening in order to liberate all beings from suffering. They say if we generate this incredible thought even once in our lifetime, it makes our whole life worth living. It really sets us on the path to awakening. It signs us up. But then we also need to put it into action. That’s the engaging bodhicitta. We want to become more engaged in the world, more compassionate, more openhearted, and more lighthearted. The world is so heavy. People are so depressed and suffering in so many ways. To be openhearted and light hearted and bring some humor into the world is maybe one of the best things we can do these days—to be friendly to the poor people behind the cash registers standing on their feet all day slogging away for, hopefully, minimum wage.

Let’s not take ourselves so seriously. We want to lighten up. Lighten up in both ways. Lighten up our hearts. Let go of some expectations of ourselves. Appreciate our good qualities and not bang ourselves over the heads for our failings, and also lighten up the world. We’ll actually be in a better position to lighten up the world because we ourselves are lighter. With a light heart, we can tread lightly in the world, which, of course, has environmental implications.

So let’s set our good intentions: to help awaken ourselves and awaken our world. We have to awaken to the sufferings of the world because that’s what helps us to develop strong compassion for the world. And that increases our capacity to help sentient beings. We can have a whole long conversation about the perils of getting involved in the world. And, seriously, if someone is in contemplation, meditation, studying in a monastery or meditating in a cave 24/7, it’s actually a breach of the Bodhisattva vows to disturb that person. According to the Tibetan lineage of Bodhisattva vows, we don’t want to disturb them. They’re on a sure course to awakening. For the rest of us mere mortals, we have no choice but to act in the world. And it’s also a great blessing to act in the world and to try to implement these amazing teachings in everyday life and in everyday actions, including difficult situations.

We can start by handing out sandwiches to the homeless. This is fantastic. This is great charity work. Then we can also take it to a deeper level, which is to try to change the system. This is more challenging. Signing petitions is easy. And we should do that. I spend a good part of my day signing petitions, but there is also a time for actually going out into the world and helping to transform the lives of the people. Figure out why we need to hand out sandwiches. Why do they not have enough to eat? Why do some 30 million children in the United States not have enough to eat? Why? What are we going to do about it? Without getting angry? I hear the Dalai Lama has a new book that says it’s okay to get angry. Actually, I learned that it’s not okay. So I’m going to have to have a conversation with him. Critical thinking, right? [laughs]

We want to awaken to the sufferings in the world, try to do something about them, and also wake up to the present moment.

I think I have taken a lot of your time. And I’d like to end by offering you all congratulations. I think you’re so fortunate, and it’s so wonderful that you’ve been able to complete your studies successfully. Now I want to challenge you. Now that you have this knowledge and these skills, I want to challenge each and every one of you to go out into the world and help make the world a better place.

And if I may, I will end with a prayer of dedication. Let’s rejoice in all of the meritorious actions we have done today and since beginningless time. The Buddhist view is enormous, huge. We rejoice in all of the wholesome actions that we have created since beginningless time, and we rejoice in all these virtuous actions and in all the wholesome actions that everyone, all sentient beings, have done since beginningless time. And since we’re in the sacred month, the fourth lunar month of the calendar, the Tibetan calendar, and also the Chinese calendar, and we’re even approaching the full moon day on which the Buddha achieved awakening, all of our actions, all of our actions of body, speech and mind, are considered 100,000 times more powerful and valuable than on any ordinary day. We generate that joy in all our wholesome actions and wholesome actions of others, and we dedicate the merit of all these wholesome actions to the welfare of all sentient beings.