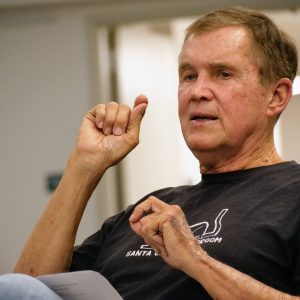

What is Sacred Space? An Interview with Prof. Doug Powers

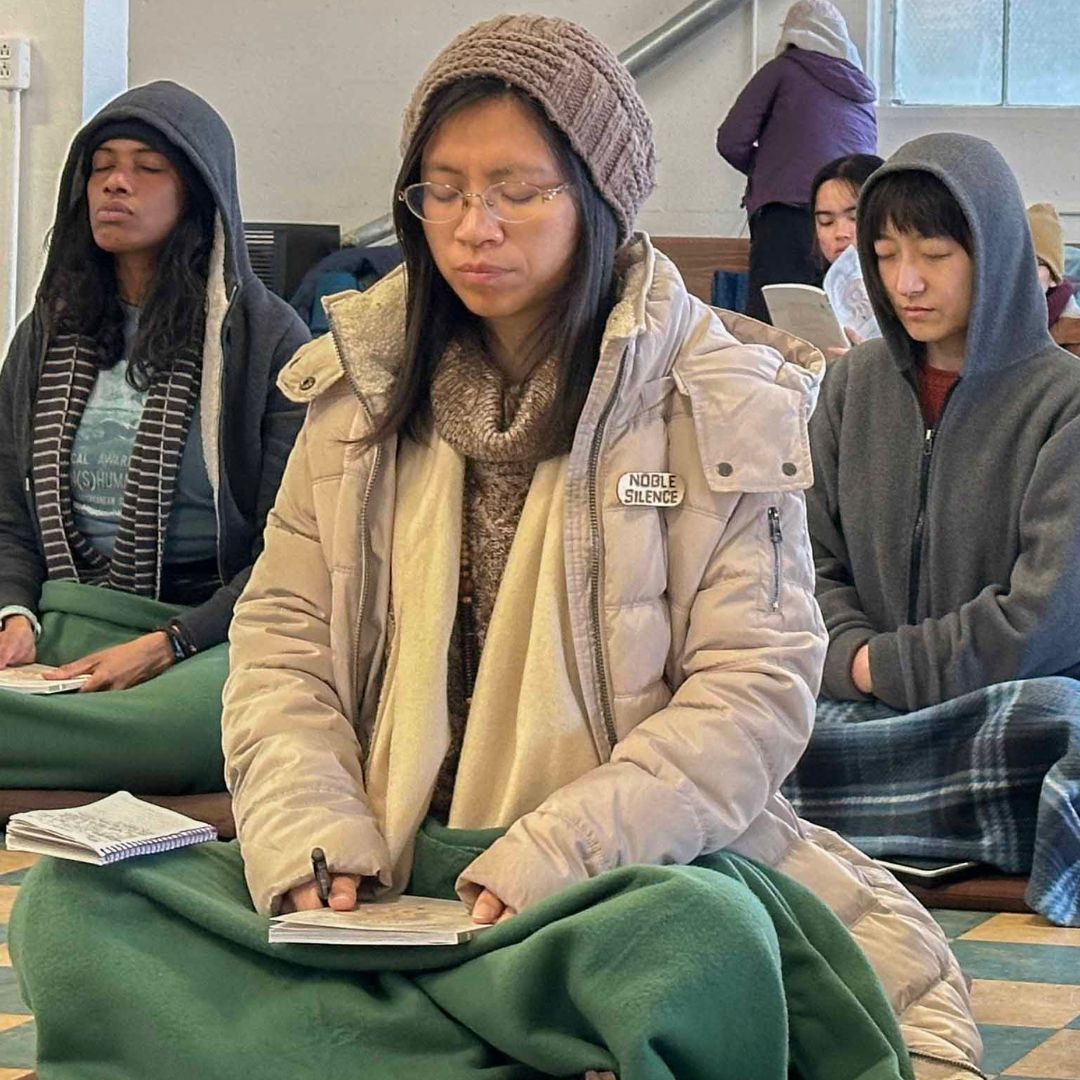

Professor Doug Powers lead daily lectures for our Fall '20 CEI on Sacred Space, and we asked him some questions about the significance of sacred space and the brahmavihāras.

I guess a good starting question is: what is sacred space?

Doug: Well, there’s probably lots of ideas about what sacred space is and we just took one approach here. The reason this was chosen was because, with everyone in their own places, with all this going on around them, to have a place where they felt like they could settle and create a space that had a different vibe to it seemed really important.

So then the question was what kind of sacred space could people create? We started off with the idea of a physical space, like a space in your house that you could set up. But then it advanced from there to a sacred space in sūtra texts, which is actually talking more about the sacred space of your mind, the sacred space of your mind-ground, the sacred space of as much stillness as you can gather, where your meditation is, where your recitation is, whatever it is that you’re doing. And that was well laid out in the Vimalakīrti Sūtra. So, we picked three or four sections of the Vimalakīrti Sūtra that suggested that sacred space is a state of mind you can achieve.

Then, we wanted to fill that sacred space with something. So, we went on to these four elements that you can find throughout Buddhism. You both create the space and fill it with this loving-kindness, compassion, sympathetic joy, and this stillness, this contented awareness, this equanimity. So we went from the idea of sacred space as a place to this open space in the mind, and then if you have that open space, to what you fill it with. And what you fill it with is this loving-kindness and so forth.

So then the relationship between the sacred space and the four brahmavihāras (loving-kindness, compassion, sympathetic joy, and equanimity) is that the brahmavihāras are what exist inside the sacred space?

Doug: That’s my take on it. I think that’s a really good idea. You could almost say this sacred space is the emptiness of the mind, but then what do you fill that emptiness with? The emptiness can be filled with these four aspects. That’s my thought about it.

So what is it that makes the space sacred? Is it the emptiness or is it the brahmavihāras that fill the space?

Doug: Well, I think it’s both. From my understanding of what the Buddha is trying to say, everything always starts in emptiness. Emptiness meaning awareness that isn’t already caught up in something. Having that free, empty space that’s aware but not habitually caught up in something which you then have no choice but to feel. I would call that the essence of sacred space. But then, in the Mahayana, once you have a sense of that space, it’s not enough to hang out in that space. You check it out and it turns out there’s other sentience hanging out there. You take a look around and you begin to see that that space is actually filled with sentience.

But before you do that, you have to create the warmth of loving-kindness. Loving-kindness creates a warmth, which is actually a kind of tone. There’s a feeling to it. It’s got a warm glow. And then the compassion is actually just paying attention. So you just pay attention in a very, very intense way to other sentience and you give it space. You give the other sentience space to exist, and then it exists. And when you pay attention you begin to see that there’s a lot of sentience. And you find out that oftentimes that sentience has elements of suffering, and you also realize that sometimes there’s a really joyful experience to that sentience. So you’re open to both the joyfulness and the suffering. But if you actually get into those, if you get into the suffering or the joy too much, it’ll muck up that loving-kindness space that’s open and free because you’ll be bummed out or you’ll be jealous of their joy. Those are the two big problems: you’re either jealous of other people’s joy, or you get caught up in their suffering. That’s where equanimity comes in. You have to get to a place where you have this sense of equanimity so you can sit in that loving-kindness in a totally open and aware way and not be moved by either suffering or joy. You can be aware of them, but not be moved by them. The equanimity is that state being aware, being open, that can engage everything that’s going on without getting moved.

So it sounds like you’re saying that the sacred space, at its core, at its essence, is interrelational. It’s not isolated from other people.

Doug: Well, in the Mahayana, starting from the Lotus and then all the way through these different Mahayana texts, the Buddha is pointing out that the practice of Nirvana is just a warm-up. Nirvana is creating the conditions to actually engage what’s going on. It’s a skillset. It’s a fundamental place where you’ve gotten out of your own conditions enough to actually pay attention to anything other than your own habituation. You have to have a certain amount of Nirvana to be able to engage with something other than your own habituation. But once you have that, if you actually look around, if that awareness actually looks around, you will find that it’s totally interconnected and that it’s a part of all this different sentience, and eventually it realizes that there’s no way to separate one sentience from another, that it’s all part of the same sentience. But this is still from the vantage point of your karmic conditions to all that sentience, so there’s a unique element to the vows that each individual bodhisattva takes. Eventually, you see that the entire conditioned existence, insofar as you’re looking at it from sentience, is all interconnected in a web where every interconnected part causes every other part. There’s no place you can look where one part isn’t affecting another part, like a crystal or something like that. And then you realize: Oh, if I want to go to the real Nirvana I have to take all this sentience with me. And that might take a while. So you probably have to have a little patience there.

This may be a result of my coming from a Western context or a Western hermeneutic, but I think of the sacred as being in opposition to the profane. And I’ve observed in myself that, when I have an experience of something as sacred, there’s an instinct to want to protect that from other people who might not understand it as being sacred, to protect the integrity of its sacredness. How do you balance between protecting the integrity of what is sacred and letting people into that sacred space, experiencing that other sentience?

Doug: Well, that depends on where we’re talking about in the process. Early on you have to protect every moment of stillness against the habituation, against the impulsive behavior. So when you first come across it, protecting whatever little bit of sacred space you have is a real challenge because it’s a little light in a huge mess that you otherwise want to get into every day. So, it depends. When somebody is first starting, they need to protect whatever they get, whatever insights they get or whatever practice they get. They do have to be fairly protective of that. But as you move into it, you find out there’s nothing really to protect because there isn’t any division between the sacred and the profane. And, you know ultimately it’s just all one continuum, and everybody, all sentience, is someplace on the continuum. And you can have a little bit of a sense of humor about everybody and yourself. You can see how everybody’s trying to do whatever they can. They’re all trying to do the best they can within their context.

How do we take these concepts and apply them to a larger scale, to the level of society or culture or community? How do we, working from our own individual sacred space, extend that out to a larger level?

Doug: Well, that’s actually probably the easiest part of it, because you’re starting with yourself. You’re trying to be consistent, within yourself, to those values, to that loving-kindness, that compassion. You just look at your own process and put that to work in yourself. Then you put it to work with the people that you’re around and you try to create community. If there’s one other person in the house, you try to do that with one other person, your parents, your family, the people that you’re already given to karmically. You always already have a karmic family. So you bring it to the karmic family first. And then you extend from the karmic family out to the larger scale. And you have to learn skills to do that. You can become a teacher, a doctor. You cannot bring it out to a larger scale from just thinking you’re doing it. You have to actually have technical knowledge. You have to have tactical approaches. And then as you bring it out and bring it out, the effect you have on the whole causal matrix of a whole region or a whole country or a whole world are as big as you can make it with your imagination and your skills and your intelligence and your strategies and your loving-kindness. Everyone has the capacity for a very large effect. Most people don’t reach a very large effect, primarily because they don’t have a large imagination of loving-kindness, or they don’t do the work it takes to make a difference in a real way. They’re just imagining something they’d like to do differently, but they’re not willing to work hard enough to actually bring it about.

So you’re saying that the limit of what you’re able to affect is just the limit of your own imagination.

Doug: Yeah, for sure.

Wow. That’s very interesting.

Doug: I mean, it’s more than your imagination, because you have to actually bring it about. It’s the scope of your awareness and then the scope of the energy you’re bringing to it, and then the actual bringing of that energy to the actual causal matrix within the conditions of that moment.

Earlier you were saying that when you start out there’s a stage you have to go through of protecting the sacred space that you’ve created. Does that happen every time you expand the scope that you’re working in?

Doug: No, I don’t think so, because once you can get the foundation, once you’ve sat enough or recited enough, whatever your practices are, once you’ve worked on it long enough and hard enough that you can count on it to be there under all circumstances, or under most circumstances, then as you’re going about doing stuff you know that you have the potential of a kind of freedom that you can always get back to.

And so, as you’re going through the day you think: Okay, this was much too much today. I’ve got to sit and just look at what I’m doing here. Then you know you can get back into that space and feel a little bit of confidence in that mental space that you can enter. You begin to get a real sense of freedom there, from conditions, from impulses. It’s all driven by that. It’s the freedom and energy within that space. It has its own energy to it, the goodness of it, the intention of loving-kindness behind it. It actually gets other positive, energetic forces behind it, and it draws other people. Just like you can see that tweeting negative stuff toward other people’s anger can draw 80 million people into an angry rage. Well, if you see how that works, why can’t you see how a real positive loving-kindness draws from people a totally different aspect of themselves? There’s no reason why that can’t happen. So, anyone here could be the opposite of Trump and be the open-hearted, generous person that draws that forth, and makes everybody feel so good about their generosity and their helpfulness.

It’s all completely malleable. I mean the whole of human consciousness is totally malleable to the conditions. There’s no hidden reality somewhere. It’s just a matrix of interaction and it’s completely malleable to the dynamics of causation.

It seems like when you practice alone or in a very protected environment, that it’s a lot easier to have confidence in that space you create.

Doug: For sure.

How do you know when it’s strong enough to be relied on when you take it outside of that space?

Doug: You poke around a little bit. You know, how’s it going with your parents? How’s it going with your friends? How’s it going when you poke out of it? If you go do something, like you teach, or you work somewhere, how’s it going? Can you bring that loving-kindness? Can you bring what you created into that space? Can you take that equanimity out to 30 kids in a classroom or do they get irritating very quickly?

So you just have to put it to the test?

Doug: You have to put it to the test. And you just have to try it out step by step. There’s no magic. You try it out and you practice. You know, I was teaching at Berkeley High at twenty-two. I had five classes of 160 kids a day at twenty-two. You have to put it to practice. Whatever you find yourself in, you have to put it into practice. You put it into practice in the world you actually live in, the friends that you actually have, the context you’re actually in, the things you’re actually doing. And when you can bring it more and more into play in those contexts that you already have, and the conditions you already have affinities with – because every condition you’re in right now is one that you have affinity with – then you can move out a little bit and move out a little bit and move out a little bit.

But you have to really watch over yourself so that you don’t get ahead of yourself and you don’t bullshit yourself and think: Oh, I’m such a great and wonderful blah blah blah, and forget what it’s all really about. It’s all just kind of a joke from a personal level. I mean, don’t take it too seriously. You’re simply trying to have this effect. You’ve got to make sure you always remember what it’s really about and don’t get into it too much.

You’ve mentioned a couple of times the importance of not taking it too seriously, of having a sense of humor.

Doug: Yeah. You’ve got to have a sense of humor. You’ve got to have a sense of humor about yourself. You have to realize that no matter how far you get in whatever you’re practicing, you’re still way far away from your potential. And when you go to try to influence the whole causal conditions, you’ve got to have a sense of humor about how much you’re actually going to affect it. You have to have a sense of humor because, in the larger causal network, the thing you’re going to affect is really a very small realm. So to overblow in your mind what you think is actually going on is kind of funny.

And then, in your own process, you’ve got to be a little bit funny. Every time you think something or get involved in something that’s ridiculous, rather than judging yourself, you have a sense of humor. You have to look at it and see it for what it is, but you also have to have a sense of humor so you’re not overwhelmed by what you’re really trying to do. Because in fact, what I’m talking about here is a pretty overwhelming thing to do. So a sense of humor protects you from taking yourself too seriously. In most cases, the best criticism of myself is my sense of humor. It’s an easier way to criticize myself. I don’t really have a super ego. So my sense of humor stands in for my superego.

You make fun of yourself a little bit.

Doug: I make fun of myself quite a bit. Yeah. I’m funny. I’m very funny. I’m a very funny person.

But it’s a benevolent kind of making fun of yourself.

Doug: Yeah, it’s benevolent. It’s being realistic. I’m just trying to be realistic. I’m not a bad guy, but let’s not get too carried away here. You’ve got to have a little sense of humor about yourself, keep things in perspective.