Explain Buddhism: Part Two

What is Buddhism? What are the teachings for? This is part two of Buddhism Explained with Professor Verhoeven.

This article is part two of an opening lecture of the second annual DRBY Canada Conference in Vancouver, British Columbia, on July 2, 2005. Check out part one.

The point I want to make is that existentially, Buddha Dharma remains relevant because these unchanging issues endure: aging, illness, death, and the search for meaning amid all of this—they are lodged right between our eyebrows, hanging over our heads all of the time. All of us face this; or we frantically try to deny it, which is another way of facing it, really. They are not going away, no matter how we want to wish them to vanish, or think that modern technology will step into the breach and be our savior.

So this is how the Buddha begins. He goes through this crisis of deeply and sincerely examining what he’s doing and why he’s doing it. The real work of “know thyself.”

Suddenly, palace life seems dead, even deadly; sensual pleasures don’t please. Accumulating wealth, making his mark, and preserving the family name—the entire worldly portfolio—doesn’t make sense.

None of this resonates with him when compared to the one great matter. The American poet, Walt Whitman, nearly 2000 years after the Buddha, posed an almost identical reflection:

Hast never come to thee an hour,

A sudden gleam divine, precipitating, bursting all these bubbles, fashions, wealth?

These eager business aims—books, politics, art, amours,

To utter nothingness?

Prince Siddhartha, with his attendant Chandaka, leaves the palace. Then what does Sidhhartha do? What is his fourth encounter?

He meets a wandering mendicant, a sramana, one who lives an austere, self-disciplined, and simple life as a way of accessing one’s spiritual nature. A wandering contemplative, he takes only enough food and clothing to sustain himself. Sramanas move around because they are cultivating an understanding that is born from lessening attachments and getting free of entanglements. They are discovering that spiritual truth derives less from external ritual and more from inward transformation. They are engaged in a mind-body yoga aimed at solving the riddles of

“Who am I?”, “Where do I come from?” and “Where do I go when I die?”

They are disengaging themselves from all the non-essential things that distract them from answering these questions—like material possessions, romance, class, career, even their own constructed identities (‘me and mine’). The approach is direct, visceral, real.

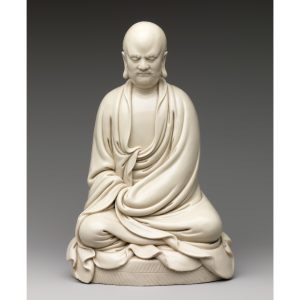

The prince doesn’t read a text, or meet a preacher, or get handed a received tradition. He encounters an individual, and in seeing that individual, he beholds something that profoundly moves and changes him. That is the essence of Buddhism: it is a living tradition that is acquired through direct experience and passed on through embodiment. The Buddha-to-be sees something that both stops him from continuing as he has been and inspires him to begin a whole new life. This is called “the great reversal.” I don’t know what that was; perhaps by its very nature the quality of this experience is ineffable, beyond words. I can speak from my own experience having encountered a great and wonderful teacher and what it did for me.

There is this feeling that such a person not only has answers, but their demeanor, the way they look, and the way they conduct themselves suggests peace, harmony, tranquility, and a kind of deep contentment and wisdom that comes through self-knowledge, and if you will, self- conquest. Both are born from examination, a disciplined critical inquiry into the nature of one’s own being and the world. The result is palpable; they exude profound joy and freedom.

And this is what the Buddha sees. It’s as if he says, “I want what you’ve got! What are you doing? How did you get this way?” In response, the mendicant simply explains this spiritual path—sila, samadhi, prajna; morality, meditation, gnosis. Inspired and guided by that, the prince then sets forth to imitate, or more precisely, to recreate or discover for himself what is so evident in the visage of this wandering ascetic.

In fact, if you want to know what Buddhism is, it is nothing more than each of us trying to replicate the awakening experience of the Buddha.

So, if you have or are experiencing a kind of angst, or uneasiness, or uncertainty, a kind of “I don’t know, it just doesn’t make sense” feeling, then you are in a very rudimentary way on the Buddha’s path; you are at where the Buddha began. Where all buddhas begin.

Don’t think that to be a Buddhist, I have to just cling to unwavering faith, or I have to know the answers to all these questions. Faith is only a beginning; it merely gets you started—knowledge is the end. The questions answer themselves as the insights come, and the insights come with practice. As a line of verse goes, “practice and understanding mutually respond.”

You have to start with the questioning, and they have to be your own questions. The method of pure inquiry is what the Dharma is all about.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get nourishing and mind-expanding writings in your inbox.