Uncovering the Sacred Treasury Within Us

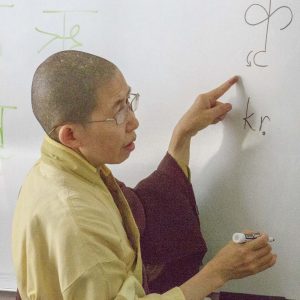

Translator profile: Bhikshuni Jin Xiang

When asked about translation as a spiritual practice, Bhikshuni Jin Xiang emphasizes the mindfulness, wisdom, and patience involved in translation work: “The translation of sutras involves considering each word or groups of words, their direct and indirect implications, and their possible effects on readers. As such, we translators need to spend time to really contemplate on the words of the sutra, much slower than just reading through it.”

“The practice of contemplation is like the practice of meditation: we dwell on the words and phrases and consider what they really mean in that particular context. After some contemplation, sometimes we find out that the words that we have read many times can have other meanings. In a team setting, we need to learn to be flexible and open. One of the lessons I learned is that it is okay for the translation to be vague sometimes, to allow the readers to have their own interpretation of the text.”

“Translation work is a form of spiritual practice because it involves practices of mindfulness, wisdom, and patience. It involves listening to others who offer perspectives that are different from our own.”

The Way to The City of Ten Thousand Buddhas

Originally from Myanmar, Bhikshuni Jin Xiang’s first language is Burmese. In school, she learned English as her second language. From her pre-teen years she recalls her mother’s effort to have her children learn more languages. “Due to my mother’s foresight, she had us learn English and Mandarin Chinese from tutors outside of school. After I arrived in the U.S. my study of Chinese paused for many years.”

Later, when a job offer after college took her to Seattle, she re-discovered Buddhism. She found inspiration and grounding in the teachings from both Theravada and Mahayana traditions and continued learning Chinese from classes and Buddhist ceremonies. Through Gold Summit Monastery in Seattle, she encountered Venerable Master Hsuan Hua.

She left the home-life in 1999 and was fully ordained in 2002. Upon arriving at the City of Ten Thousand Buddhas in 1998, she taught at the Developing Virtue Girls School. Since then, she has worked in the Office of the Registrar at Dharma Realm Buddhist University (DRBU) until now. In 2014 she completed her MA in DRBU’s legacy program. She graduated from the Translation Certificate program in 2022, which not only gave her new perspectives in translating sutras but new ways of looking at language—the concepts and power behind words.

A Journey in Words

The first time she started working with translation was in May 2006, four years into her life as a fully ordained nun. She recalls how translation became a part of her work: “As someone who has always needed English translations and being proficient in English, I was given an opportunity by one of the senior nuns to work on the editing of a sutra text in English.“

“I think the first sutra project I was given was the Ten Thousand Buddhas Repentance text. Later on, I worked with a fellow English-speaking nun on chapter 38 of the Avatamsaka Sutra, eventually producing a provisional version for recitation purposes. It was quite a revelation and a joy to be able to translate and gain insights into what the Buddha said.”

“I was not and still am not proficient in interpreting Chinese texts. At the beginning of my translation journey, I mainly worked on editing draft English translations. Whenever I had a doubt about the English translation—due to the meaning of the English word or sentence structure not being clear—I would look up the Chinese word in a Chinese dictionary or find a Chinese speaker to clarify the meaning. (My previous Chinese knowledge came in handy.) I would even look up the corresponding text in the Chinese sutra text. In my early years as an editor, I was working on my own or with another English speaker, so I didn’t really have a guiding principle per se. It was always based on how the English words made sense. If I had a doubt and couldn’t resolve it through editing the English, I would go to the Chinese source to get a better understanding before editing.”

Listening as a tool

“In recent years, the guiding principle for me as a team member in selecting different choices is to be mindful of the future readers while being mindful of the Buddha’s intent when he taught the sutra. That way, we can match the translated text to the Buddha’s intended meaning. Being mindful of the future readers means to be aware of their culture and how they use their language. It also means to be aware of the effect of the translated text and how the sound of recitation of the translated text would have on the listener.”

Bhikshuni Jin Xiang says listening to what you have just translated, is a very useful tool. “In our group translation outside of the Translation Certificate program, when we finish translating one paragraph, we read it out aloud,” she says. “Often we find minor mistakes or something that needs tweaking. From this experience, I found that in addition to reading the translated text, hearing the text immensely helps as a filter for catching mistakes or mistranslations.”

Another indispensable tool in translation is the glossary management: “One of my team members was assigned to work on glossaries. The way we determine what should go into a glossary is the frequency of a term or phrase in the sutra text. It is important that we translate the same terminology the same way in the same sutra or across different sutras. The glossary serves as a reference for future translations, making it more efficient. It is a valuable resource for both long-time translators and newcomers to BTTS.”

The translations of the Buddhist Text Translation Society (BTTS) are always worked out in different committees – how would you say this team working method influences the final, certified translation?

“I usually work at the Editing or Group Editing stage. In the Translation Certificate program, we keep all the previous versions in one file, so I can sometimes see the difference between these two versions—how the Editing version has been improved a lot in the Group Editing version. In group-editing, we do a lot of polishing in terms of meaning and linguistics. Even at the group-editing stage, when our team cannot resolve some issues, we come up with some options to help the certifier(s) make the final decision.”

“With the four committees—Primary, Review, Edit, and Group Edit—serving as filters, we can be certain that the final translation will be of high standard.”

When asked about what distinguishes BTTS’s method of translation, she points to the central role of the guidelines. “The BTTS/IITBT’s approach to translation requires a lot of patience and openness from the translators, who are also practitioners. They follow the BTTS guidelines, which basically ask translators to be true, humble, considerate, and public- spirited persons,” she says.

Continuous Learning

Alongside working with translation, Bhikshuni Jin Xiang has also become proficient in Sanskrit, a long project she embarked upon just after she first arrived at the City of Ten Thousand Buddhas.

“Learning the Sanskrit language was not easy. When I first joined DRBU in 1998, I was fortunate to have been a student of a few dedicated Sanskrit teachers/experts who could impart their linguistic knowledge and wisdom. Taking a lot of notes by hand was a way to remember and organize the detailed concepts. I also created tables and flowcharts as learning tools for myself and others. I learned later that the alphabet system of Sanskrit was the same system used in the alphabet of Myanmar language, which was an advantage for me in being able to pronounce several unique Sanskrit sounds.

As language learners already know, it was the continuous learning (even during summer) that made it possible for me to memorize scripts and become more familiar with the complex rules of Sanskrit sounds and grammar. I was able to contribute my knowledge and research skills to proofread the new Śūraṅgama Sūtra. I also helped decipher Chinese transliterations of Buddhas’ names in Sanskrit in the Ten Thousand Buddhas Repentance text. Teaching a class has given me a chance to polish my learning a little bit more.”

A Way to Uncover the Sacred Treasury Within Us

Would you like to share some advice for people who are interested in translating Buddhist texts?

“This is what I have to say to those interested in translating Buddhist texts: Translating sacred texts is a way to uncover the sacred treasury within us. It is the gateway to activating your inherent nature. The merit of doing this work is manifold. Not only can you get to read the sutra text, you also get to meet fellow spiritual friends. In addition, you gain broad exposure to theories and principles used by translators from ancient times, other traditions, and other cultures.”

“Working with fellow translators has been especially rewarding for three reasons: (1) learning from knowledgeable native speakers (e.g., Chinese or English) who can convey subtle variations of words or sentence structure; (2) exchanging different ways of seeing and translating; (3) knowing that we have tried our best for the sake of awakening ourselves and others.”