The Essentials of Self-Cultivation Haven’t Changed Over Time

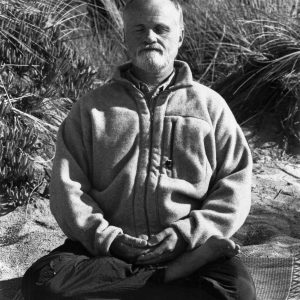

The following is an excerpt of Professor Martin Verhoeven’s talk as part of the university’s Self-Cultivation Check-in program offered by the Spiritual Life team on April 26.

The essentials of cultivation haven’t changed over time; it still boils down to this:

all beings have the buddha nature and all can become buddhas.

It is only because of our grasping and muddled thinking we do not realize this potential.

Master Hua opened my first Chan session with this verse. It really touched me; struck home; went straight to my heart:

“Living beings grasping everywhere,

Cover over the wondrous.

Let go, release your hold!—

The wondrous revealed!”

This is the essence of the teachings and key to liberated awakening.

Cultivation is cultivation—in the buddha hall, in the apartment, on the bowing cushion, in the car, alone in a cave or in a crowd, in the bathroom or the boardroom. There is no place that isn’t the place of awakening (Bodhimanda), and there is no time that cultivation stops.

When Dharma Master Heng Sure and I began our bowing pilgrimage, we were nervous, unsure of ourselves. We had bathed in the supportive atmosphere of the monastery, like a cocoon of security and safety in which to practice. Now as we stepped out onto the streets of Los Angeles, alone and no longer sheltered by the daily rhythms of monastic life; the ceremonies, Dharma friends, an ever-attentive wise teacher, we felt vulnerable, small, exposed and shaky. Master Hua told us, “On highway be as if never left monastery.” And then, after 2 ½ years of bowing and living on the highway, we felt trepidation upon finally arriving at the journey’s end: the City of Ten Thousand Buddhas. How could we readjust to living inside, in close quarters with others again, so removed from our primary practice? Shifu greeted us at the front gate, and said, “When you are in monastery, be as if you never left highway.” This is the non-dual teaching of all Buddhas: all places are the same place, all time is the same time. It is the mind itself that is the Way Place.

The great scholar-monk wrote about this in a long letter he penned to an official back in the time of Shakespeare. The official worked along Han Shan doing famine relief in China, and was so impressed with the Master’s virtue and demeanor that he later wrote to Han Shan, asking “what is this thing called Buddhism. . . and the ‘one great matter’ you spoke of. . . and what are the essentials of self-cultivation?” Han Shan replied in this remarkable essay to him, laying out the essentials. Although the letter is over 400 years old, its message and meanings are timeless and timely then as it is now; unchanged and unchanging.

“You asked about the meaning of ‘the causes and conditions of the Great Matter.’ First of all, the Buddha-nature is innate and whole within all of us, present here and now, and lacking nothing. However, since beginningless time, the deeply rooted seeds of craving, deluded thinking, emotional anxiety, and ingrained habits have all polluted and obscured its wondrous brightness; thus, we cannot realize its full expression.

. . . If our deluded thoughts can be stopped and dissolved, our true mind will naturally manifest, as if we were polishing a mirror. In the same way, once our defilements are cleansed, our bright wisdom will shine forth. This is what the Dharma is all about.

Unchecked over time, however, these unwholesome tendencies habituate, harden, and solidify. At the root of this is self-clinging. This root is deep and difficult to pull out. Fortunately, in this life, we can rely on our inherent wisdom–a fragrant seed within. With the guidance of a good knowing adviser as the external catalyst, we realize that we have had such wisdom all along. We set our mind with a determination to liberate ourselves from the cycles of rebirth and death. But if we want to pull out in one stroke the root of rebirth and death, which has grown deep over measureless time, how can this be a simple matter!?

Unless you are a person of immense strength, who is able to shoulder a heavy burden and pierce to the heart of the matter as with a single saber thrust, this task will be extremely difficult. The ancients compared it to “a lone warrior going into battle against ten thousand enemies.” These are no mere empty words. . . ”

So, every day, every moment, is the right time for cultivation.

It is like being in a Chan session, except the Chan session never ends; it just changes locales. Self-cultivation is 24/7. This is what the Sixth Patriarch, Huineng, meant by the “great samadhi” where “One neither enters or comes out of this samadhi concentration, it cannot be settled-into or disturbed.” He called it literally the “single-mark samadhi,” explaining,

If you do not attach to appearances wherever you are, and do not become attracted to or averse to them, neither grasping nor rejecting, and are untroubled by gain, success, failure and the like; but instead, in the midst of all things remain calm, composed, fluid and adaptable; modest and not aggressive, quiet in mind with few desires, then you have mastered the “single-mark samadhi.”

So over time, over millennia, self-cultivation has the same principles, though different particulars – China, India, America, Europe, Chan hall in the small arena, outside world in a big arena. None of this matters; it is the same mind, this very here and now mind that is the ground of everything else.

I am sometimes amazed how little has changed, in both our confusion and afflictions, and in the methods to cure them. The deep essentials remain the same, only the superficial surface varies.

We can feel we are doing something cutting edge, really far-out, and radical; but we are just walking the same path every buddha walked, that every sage and cultivator from time immemorial has walked, is walking, and will walk: sila (morality/virtue), samadhi (steadiness of mind/equanimity), prajna (wisdom) countering our greed, animosity, and confusion. The Buddha had his palace, toys, duties and diversions; and we have ours. But beneath it all, it’s the same old story. But that doesn’t mean it’s easy, or just because they did it, we somehow be ushered in on their coattails, so to speak. No matter how sincere we are in wishing to get enlightened and gain wisdom, wishing doesn’t cut it. Only actually doing the work decides. As it says in the Dhammapada:

“No one frees you but yourself/

no one can, no one may.

You yourself must walk the path,

buddhas only show the way.”

Each step forward along this path is a wonderful thing; hard won, immensely liberating and joy-filled, like nothing else we can ever experience. It has an exquisite taste. Like Ananda once described to the Buddha “Lord, it’s as if a man — overcome with hunger, weakness, & thirst — were to come across a ball of honey. Wherever he were to taste it, he would experience a sweet, delectable flavor.”

But the habit-energy of letting things slide for so long, of neglecting our true nature, like the force of gravity, pulls us back with each step forward. After my first session at Gold Mountain Monastery, I was so happy and liberated. I felt as if I was floating on a cloud. Then I left the monastery to go back home, and after a few days, actually within just a few hours, I fell out of my cloud and hit the hard pavement. I lost my wings. My old habits pounced on me (or so it seemed) and I felt defeated. A few days later I went back to the monastery, and was met by Master Hua as soon as I opened the front door. “What’s up?” he asked smiling and looking straight into my dejected face. I answered,

“Shifu, this is hard, harder than I thought. Can you give me a special dharma, a power tool?”

Master: “Your teacher is not particularly talented. I don’t have any secrets or shortcuts. I only know this one method: Patience and hard work; perseverance and patience.”

Me: “Really, that’s it!?

Master: (pausing and looking me square in the eyes: “Actually, though, there is no other method. I’d be cheating you if I told you differently.”

Master: “Do you understand?”

Me: “I am not sure. . . “ I paused. “How will I know if I am making any progress?”

He sat down next to me and explained,

“You should think this way: ‘Every day I eat, sleep, put on clothes; every day I cultivate.’ See it as ordinary, regular, just what a person does, what a person is supposed to do. Then you will make progress for sure.

Don’t worry about making progress, just worry you won’t practice. If you practice every day, walking, standing, sitting, lying down, even if you don’t want to progress, you will.

But if you sit around worrying and wondering about making progress or if you are falling behind, you won’t move an inch. Just try your best.”

Then he pointed to the handmade wooden sign above the exit of the monastery’s front door, which said,

‘TRY YOUR BEST’!

This sign exhorted you to “try your best” when leaving the temple and going out in the larger world. “Watch your head! Take care!” And when coming back into the monastery there was another check-in verse we came to hear quite often:

Everything’s a test

To see what you will do.

Mistaking what’s before your eyes,

You’ll have to start anew.”