This article is adapted from our recently published video essay on Pure Land Buddhism, created by one of our alumni.

If you were to go to China or Japan and you asked a random Buddhist what kind of Buddhism they practiced, it’s very likely that they would say “Pure Land Buddhism.” Pure Land Buddhism is by far the most widely practiced form of Buddhism in East Asia, and there are good reasons for that. It is considered to be the “easy path” to enlightenment, a method that everyone can practice even in the bustle of a busy life. Generations of revered masters have used and recommended this method of practice. Yet Pure Land Buddhism remains relatively unknown in the West.

The general idea of Pure Land Buddhism is relatively straightforward. There is a buddha called Amitabha, who out of compassion for all suffering beings created a world called the Land of Utmost Happiness. Beings who are born there never experience any suffering and are constantly surrounded by great awakened beings and by the teachings of the Buddha. Even the birds are said to sing the Dharma. Those who are born there never fall back on the path to awakening and are assured of eventually reaching buddhahood.

Amitabha Buddha’s promise is profound: if you sincerely recite his name with faith, especially at the time of death, you will be reborn in this pure land.

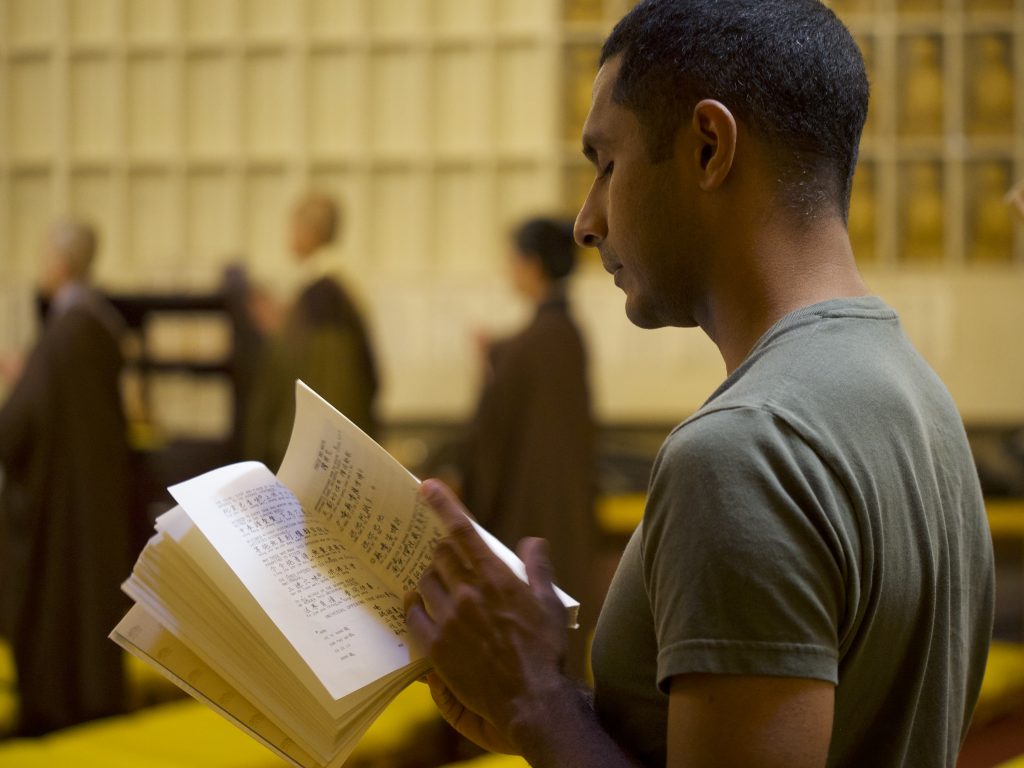

Amitabha’s vow has inspired countless practitioners throughout history to rely on the recitation of “Namo Amituofo” (the name of Amitabha Buddha in Chinese), a simple but powerful practice that can be performed anywhere, even amid the noise and distractions of daily life.

At first glance, Pure Land Buddhism may seem like a departure from other forms of Buddhism that emphasize direct experience and rational investigation of the mind. One of the reasons Buddhism has become popular in the West is because it is often perceived as rational, even scientific. It does not rely on believing in a dogma but rather on personal experience. So what’s going on here? Is Pure Land Buddhism a deviation from the original spirit of Buddhism? Or is it a distillation of its main tenets in a way that is easy to understand and practice?

Pure Land practice is mainly outlined in three sutras or discourses of the Buddha: the Contemplation Sutra, the Greater Amitabha Sutra, and the Smaller Amitabha Sutra, which is recited daily in many monasteries in East Asia. A number of Indian commentaries also lend legitimacy to Pure Land practices, including a section of the Treatise on the Ten Bodhisattva Grounds, a text attributed to Nagarjuna. In this text, Nagarjuna describes what he calls the difficult and the easy paths of practice. The difficult path is to engage in the practices of austerity, meditation, ethical conduct, and self-sacrifice over many lifetimes. The easy path is to seek birth in a pure land. However, it wasn’t until these texts traveled to China and then Japan that the Pure Land tradition came more or less into the form in which it is practiced and understood today.

In order to make sense of the Pure Land method, it’s helpful to take a step back and put it into context with the wider principles of the Buddha’s teaching. It’s important to ask: what is Buddhism fundamentally about?

The fundamental premise of Buddhism is that all living beings are trapped in a dissatisfying and self-perpetrating state called samsara. The nature of this state was summarized by the great Indian Buddhist philosopher and poet Shantideva, who wrote: “Although wishing to be rid of misery, living beings run toward misery itself.”

The Buddha realized that there’s a way to stop the cycle of suffering and confusion and to attain real peace and happiness: nirvana. However, although we all have everything we need to achieve the state of complete liberation, in practice it requires us to let go of some of our most cherished habits and assumptions, like believing that we exist as an independent, enduring self, or reacting with attraction and aversion toward things in the world.

How can you go from being totally engrossed in a story about yourself and the world to complete freedom of mind? Pure Land Buddhism offers an approachable solution to this dilemma.

The main practice in Pure Land Buddhism is to recite the Buddha’s name with concentration and sincerity. One advantage of this approach is that the mind has a distinct point of focus. In Chinese Buddhism there’s a saying: the Pure Land method is fighting poison with poison. Although, when we are reciting the Buddha’s name, we are still doing so as an ordinary being, we are making skillful use of a conditioned thought. We are using what is not real to go toward what is ultimately real.

If you’re still not convinced, that’s not surprising. To really see how the recitation method makes sense, we need to go a bit more deeply into a few philosophical ideas in Mahayana Buddhism.

There’s a fundamental problem with our picture of samsara and nirvana. It’s still presenting them as two distinct states. According to Mahayana Buddhism, this is quite misleading because actually the ordinary mind of samsara is the mind of awakening. As Nagarjuna put it in his Verses on the Middle Way, “There’s no distinction whatsoever between samsara and nirvana. There’s no distinction whatsoever between nirvana and samsara.”

Thus, it would really be more accurate to picture these as two sides of the same coin.

Awakening is the state that is beyond all conditions. It is by definition not something that can come into being or that can be attained. Anything that is subject to arising is subject to ceasing, and is therefore conditioned.

So if awakening was something that could be obtained or could come into being, then it would not really be awakening.

And if awakening doesn’t come and doesn’t go, then we have to concede that it’s been here all along. This may seem like a play on words, but it’s actually pointing to a profound principle, which is that the aim of our practice is not to go anywhere or to attain anything, or even to get rid of anything, but rather to learn to see differently what is already here and now.

If we take this principle to heart, then the idea of calling on the Buddha suddenly doesn’t seem so far-fetched. After all, we’re simply calling on something that is already present here and now. Something that is natural to us. Perhaps the most natural thing to us.

Therefore, when we call on the Buddha, it’s almost like we are saying, “Yes, I know that I have all these confused thoughts and habits that result in so much suffering, but that’s not really who I am. At some level I am confident that my true home, the true condition of my mind, is the Buddha. It is wisdom, compassion, and freedom. So let me call upon that.”

This is a good place to take a pause. There are still many more questions to address: How do you actually practice the Pure Land method? And is the Pure Land a real place, or is it only a metaphor? Explore these questions with us in part two.

Enjoying what you're reading?

Receive nourishing, mind-expanding insights straight to your inbox.